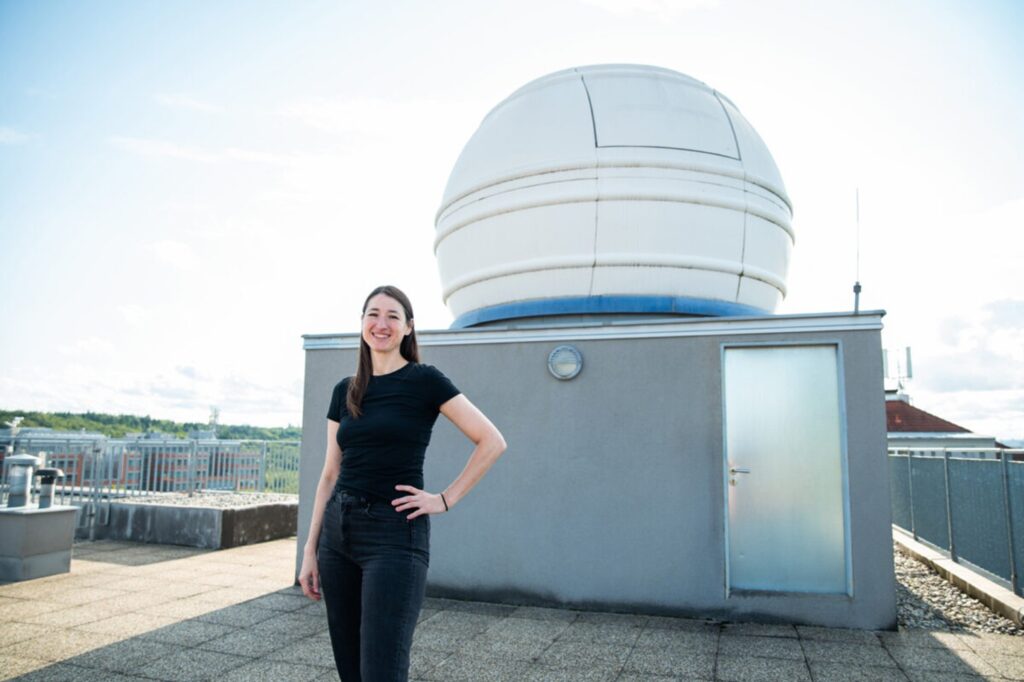

Who are we and where do we come from? These are the questions posed by Austrian astrophysicist Josefa Großschedl, who, thanks to the MERIT fellowship of the Central Bohemian Innovation Center, works at the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences. In this interview, she explains what satellite Gaia has revealed about star formation, why the Orion region and the Scorpius–Centaurus association hold the key to understanding stellar birth, and what brought her to the Czech Republic.

How do stars form?

Stars are born in giant molecular clouds—dense, cold regions of interstellar gas and dust. You may have seen images of such clouds, like the nebulae in Orion or Carina, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope. These nebulae glow because massive young stars ionize the surrounding gas.

When parts of the cloud become dense and cool enough, gravity overcomes internal pressures caused by heat or turbulence, triggering collapse. A dense core forms, from which a protostar develops, surrounded by a shell of gas and dust. Due to conservation of angular momentum, a rotating circumstellar accretion disk—also known as a protoplanetary disk—forms around the young star. This disk feeds gas into the star and gives rise to planets. Once the protostar’s core becomes dense enough, nuclear fusion begins—and a star is born.

The presence of protoplanetary disks around young stars also explains why planets in our Solar System lie roughly in a flat plane. They are remnants of the disk that once surrounded our protosun about 4.5 billion years ago.

Which phase of stellar evolution do you focus on?

The aim of my research is to better understand the early dynamical evolution of young stars—how they move, interact, and disperse after their birth. This dynamics is closely tied to broader questions about how stars and planetary systems form under various environmental conditions.

I focus on regions relatively close to the Sun—within about 3,000 light-years. That may sound vast, but for astronomers, it’s quite near, allowing for the highest measurement precision. Within this range, several important star-forming regions exist—such as Orion, about 1,300 light-years away, which is the nearest site of massive star formation. Massive stars—those at least eight times the Sun’s mass—are rare and short-lived, making Orion a key reference point for studying these cosmic giants.

Do you study any specific stars?

Yes, I study the Scorpius–Centaurus (Sco-Cen) OB association, located near the constellations Scorpius and Centaurus. An OB association is a loose grouping of relatively young, massive stars of spectral types O and B—the hottest and brightest stars, which live briefly and thus mark young regions of the galaxy. Sco-Cen is the closest OB association to Earth, only 400–500 light-years away, and still forms low-mass stars. It is therefore an ideal laboratory for studying stellar formation and early stellar evolution.

The Gaia satellite gave us key pieces of the cosmic puzzle

What data do you use for your research?

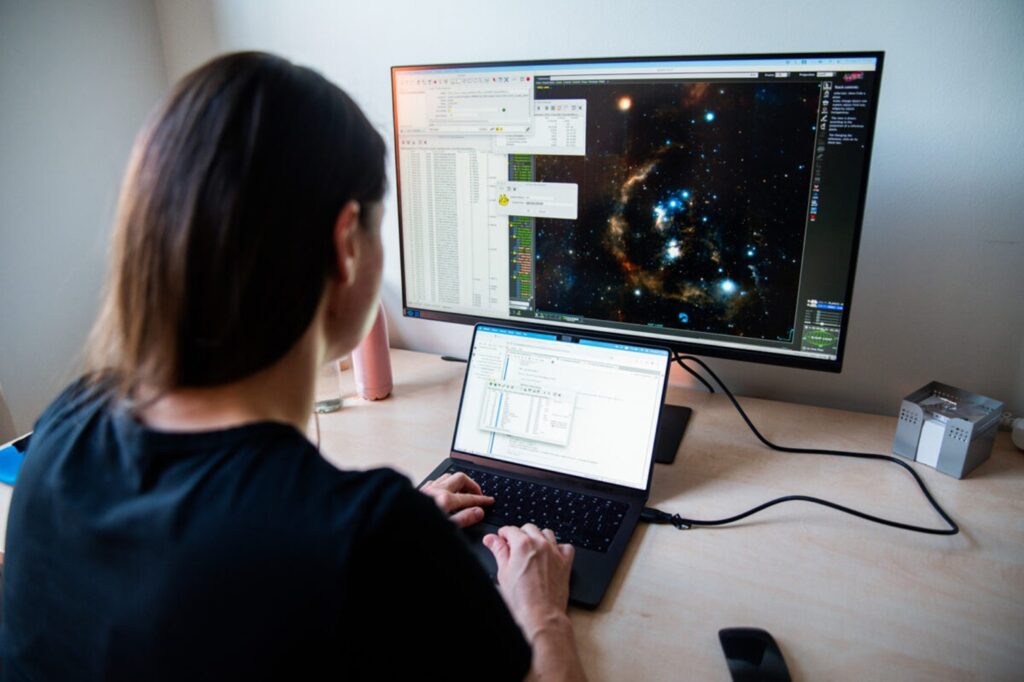

My primary dataset consists of open-access astrometric data from the Gaia satellite, operated by the European Space Agency (ESA). These data are collected and processed by ESA’s Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC). Since 2016, three major data releases have occurred, each adding more stars and improving data quality. Two more releases are expected, the next one by late 2026.

Will there be no further data from Gaia?

Gaia has recently completed its observational phase. Over ten years, it repeatedly scanned the entire sky, measuring precise positions, motions, parallaxes, brightness, and colors of stars. From these, we can infer additional properties such as mass and age. Thanks to Gaia, we now have the most accurate 3D map of the Milky Way, including the spatial distribution of young stars, gas, and dust in our galactic neighborhood.

What are the key findings of your research?

We discovered that younger groups of stars in Sco-Cen differ from older populations not only by age but also by systematically faster outward motion—an organized expansion. This suggests that star formation proceeded gradually, from the inside out. Previously, this was only a theoretical concept; Gaia provided the first clear observational evidence for such propagation.

By measuring velocity dispersion—how stars move relative to one another—we found a temporal pattern: dispersion increases over time in discrete jumps, corresponding to successive episodes of star formation. Each generation of stars appears influenced by its environment, such as supernova explosions, which reshape surrounding gas clouds and can trigger further star formation. Today, Sco-Cen shows the final stages of this process, with gas largely dispersed and only low-mass star formation continuing in remnant clouds.

To test these hypotheses, I collaborate with colleagues at the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, who specialize in gas dynamics modeling. By combining observations with theoretical models, we aim to reconstruct the physical mechanisms driving this gradual, outward-propagating formation of stars. It’s like assembling a cosmic jigsaw puzzle—and Gaia has given us the key pieces.

Why is this research important?

By understanding how and why stars form, we understand our own origins. Every atom in our bodies was once part of a star or created in star-powered processes. Our Sun formed in a similar environment to those I study. Thus, by studying star formation, we gain insight into the history of our Solar System and the mechanisms that shaped planets and life—both on Earth and elsewhere in the Galaxy.

Moreover, the methods we use—from Gaia astrometry to advanced data analysis—push the frontiers of both astrophysics and data science, influencing fields like machine learning and algorithmic development.

Astrophysics is a deeply human science

How did you come to the Czech Republic under the MERIT fellowship?

While searching for a postdoctoral position, I contacted Richard Wunsch, one of my current supervisors at the Astronomical Institute, who suggested I apply for the MERIT fellowship. The evaluation process took some time, so I initially joined the University of Cologne. After a year, I learned that I had been awarded the fellowship, and I decided to move to the Czech Republic to focus more deeply on my research. I now collaborate with experts in modeling and simulation of star formation, an area in which I wish to expand my skills.

As part of MERIT, you will also visit institutes in Berlin and Florence. What will you do there?

From October 2025, I’ll spend four months at TU Berlin, working with Dieter Breitschwerdt’s group, which studies the evolution of massive stars and the elements created in their explosions. They also investigate supernova outflows that may have reached our Solar System and Earth. Measurements of the isotope iron-60 in deep-sea sediments indicate it could be 2.5 million years old, originating from Sco-Cen supernovae. At TU Berlin, we will combine my knowledge of the local Milky Way structure with their radioisotopic dating expertise to better understand the effects of cosmic weather on our Solar System.

And your stay in Florence?

At the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), I will work with Germano Sacco on spectroscopy. He leads the 4MOST observing program, which uses a 4-meter multi-object spectroscopic telescope operated by ESO. It will measure spectra of many stars simultaneously, providing radial velocities, temperatures, spectral types, and chemical compositions—complementary to Gaia data. The ESO 4MOST survey begins next year, with the first data expected by late 2026, coinciding with my planned fellowship in Florence. The spectrograph is being installed at the VISTA telescope in Paranal, Chile. Working with Germano will give me front-row access to the first data and insight into their processing techniques.

Would you like to visit the telescope in Chile?

Yes, I’ve already been there once—to observe at ESO’s Very Large Telescope on Paranal. I had that opportunity thanks to my former supervisor João Alves in Vienna, who supports young students in visiting observatories. It’s a breathtaking place, with a radiant night sky and the Milky Way stretching above you. I’d love to return someday. However, many observations today are conducted remotely, with research teams on-site executing accepted proposals.

How long will you stay under the MERIT fellowship?

The MERIT fellowship lasts 2.5 years, so I will remain in the Czech Republic at least until February 2027. In the future, I plan to continue studying how gas and stars interact and how feedback from massive stars shapes further star formation. I also aim to engage in science outreach, help communicate our research to the public, and mentor students interested in astrophysics.

Can you imagine staying in the Czech Republic after the fellowship? How do you find it here compared to other countries?

The Czech Academy of Sciences provides a well-organized and supportive working environment. Compared to my previous positions in Vienna and Cologne, the group here is smaller, allowing for more focused collaboration. In Austria and Germany, I also had teaching duties, which were valuable but time-consuming.

Life in Prague has been enriching, though every place has its character. I sometimes miss the cycling infrastructure and vegetarian options I enjoyed in Vienna and Cologne. I was also surprised that the Czech Republic is not more sustainability-oriented—something I personally value highly.

In the long term, I may return to Austria for family reasons, but my time in Prague has been and continues to be deeply enriching, both professionally and personally. I truly appreciate the experiences I’ve gained here.

Josefa Großschedl is a fellow of the MERIT fellowship of the Central Bohemian Innovation Center, working at the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences (ASU). Her research focuses on star formation, young star clusters, their dynamic evolution, and their relationship to molecular clouds. She previously worked at the University of Vienna (Austria) and the University of Cologne (Germany). Her earlier research included studying the Orion star-forming region, the nearest massive star-forming area to Earth—a key laboratory for understanding stellar birth. At Cologne, she also taught, gaining valuable experience working with students. She continues to collaborate with researchers across Europe to deepen our understanding of how stars and clusters form and how they shape our Milky Way Galaxy.